Birds

So Much More

We love our Samarkand campus with its 16 acres of cultivated gardens and trees located on a knoll above Mission Creek with wide views of the mountains.

But there is so much more.

Our one-acre native plant garden captures the floral beauty of coastal California. A fountain made from a sandstone boulder attracts birds to drink and bathe and is a lovely place to sit overlooking the garden with the mountains beyond.

Samarkand is also an arboretum with its 350 trees, many of which are labeled. There is an accompanying Tree Map available in the nature corner in the library. On the self-guided tour, as you linger at each tree, you can imagine the complex system of roots underfoot and the miles of fungal fibers uniting them.

The nature corner in the library features books and field guides on the natural history of our area. You will also find a weather monitor that gives real-time weather specifically for our campus. Our Samarkand weather station is located on the roof of the Mountain Room.

Our Avian Fellow-Traveler, the House Sparrow

By Ted. R. Anderson

The House Sparrow originally inhabited a broad geographic region stretching across Europe and North Africa and throughout most of Asia except mainland China. It lived in close association with people in both rural and urban communities and is now often referred to as an “obligate commensal” of human beings, meaning that it is dependent on its human neighbors.

The House Sparrow originally inhabited a broad geographic region stretching across Europe and North Africa and throughout most of Asia except mainland China. It lived in close association with people in both rural and urban communities and is now often referred to as an “obligate commensal” of human beings, meaning that it is dependent on its human neighbors.

When large numbers of people fled Europe in the mid-19th century to live on other continents, many missed their familiar avian neighbors, including the House Sparrow. In the mid-1800s, 100 sparrows were brought to the United States from England aboard the Europa and released in Central Park. With the help of subsequent introductions, the species spread across the continent, making their way to the Pacific coast by 1915. Similar introductions followed in Australia, Argentina and South Africa. Range expansions increased widely from each of these sites so that today the House Sparrow is widely distributed on every continent except Antarctica.

The House Sparrow is not common on the the Samarkand campus, but a lone male does spend much of each day repeatedly chirping near the entrance to our Smith Health Center, hoping, no doubt, to attract a female to his chosen nest site. My favorite place for sparrow-watching, however, is Renaud’s. Carol and I each order one of their fabulous pastries and a cup of coffee and sit in the outdoor patio. There I watch the sparrows hop around under the

tables picking up crumbs that fall to the ground as patrons eat their pastries. Clearly sparrows have good taste!

Ted Anderson is a retired professor of Avian Biology, and the author of “Biology of the Ubiquitous House Sparrow” (Oxford University Press). The watercolor of the house sparrow (above) was painted by Carol Anderson, Ted’s wife.

Phila Rogers is now 96 years old and legally blind. She has decided to occasionaly have some guest columns of which this is one.

My New Nest

It wasn’t that I outgrew my Eastview apartment, with its spacious rooms and expansive views, it outgrew me. With my dimming eyesight, I no longer could see the Mission bell towers and could barely discern the shape of Montecito Peak. From my new apartment at Brandel Hall, I have a pleasant view of trees, south sun, and flocks of musical goldfinches. Instead of woodpeckers visiting my suet, I have overwintering warblers with their more modest appetites.

Moving to a studio apartment, gave me a chance to “lighten my load.” I kept my favorite painting of a snowy mountain range with an Indian encampment in the foreground inspiring me to decorate my apartment in a style I call neo-tepee, allowing me to use my collection of hanging rugs, pots and woven baskets.

I am not the only January nester. The small Anna Hummingbirds and the large Great Horned Owls also build their nests in January. The hummingbirds fashion their nests from grasses and spiders web decorated with lichens while the owl builds a casual structure from sticks piled up in a tall tree.

Autumn In Santa Barbara? Yes!

Maybe we can’t brag about brilliant splashes of color everywhere like they can back east, since Fall is subtler in California, but there are still clear signs that the seasons are changing. As the days grow shorter, shadows grow longer, giving a rich, baroque look to the landscape. The air achieves a balance between the cool, damp marine flow and the drier air of the mountains. The breeze has a tantalizing sweetness of ripening fruits and crumbling leaves.

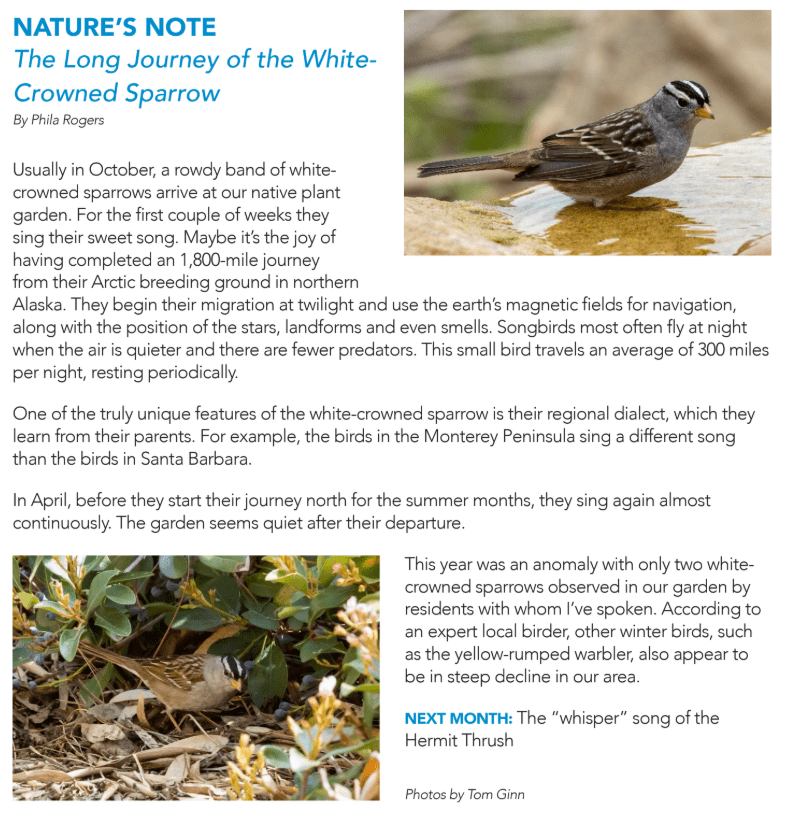

In the Native Plant Garden behind Eastview, you’ll see the billowy bushes of the Toyon, whose succulent berries will be red by Christmas. Further down is the sprawling “Roger’s Red,” a subspecies of the California wild grape. The White-crowned Sparrows arrived in October and fill the garden with their sweet songs.

In Oak Park, the leaves on the big sycamores are tawny now. Around town, you’ll see liquid amber trees, with a palette of oranges and maroons, and the ginkgo trees will soon turn a pure brilliant yellow. The lone survivor of an ancient species, these trees shared a landscape with the dinosaurs.

Fall is not just about plants. It’s also about critters—the big Orb Weavers that weave symmetrical webs and then plant themselves in the center waiting for trapped insects. And if you find yourself in the dry country, look for the astonishing sight of tarantulas on the trails in search of mates.

Two Red Rocking Chairs

As you approach the entrance to buildings Northview and Westview, your eyes may be drawn to two red rocking chairs on a small patio in back of Sylvia Casberg’s apartment. The patio is surround by a simple wrought iron fence and a gate that is always open. Potted red geraniums hang from the eave and two beautiful wind chimes make music in the lightest breeze. A curving pathway of crunchy white gravel leads to the street. A white pottery birdbath attracts birds and the attention of photographer Tom Ginn. In early summer the garden features a bird of paradise plant surrounded by California Poppies and orange nasturtiums. Later, saucer-sized red- orange hibiscus attracted watercolorist Sue Fridley, whose painting is featured here.

Asking about Sylvia’s early garden experience, she said, “As a child I was encouraged to grow a Victory Garden but only radishes came up which I figured weren’t going to win a war. I had better luck when nurseries began offering small plants. I talked to the plants reminding them that ‘you grow or out you go.’”

If you walk by early in the morning, you may see Sylvia wrapped in a blanket enjoying a cup of coffee. Later in the day it might be a glass of wine sipped as she enjoys the sunset.

More About Interspecies Feeding Among Birds

Dear Friends:

In order to do justice to Ann Allen’s lovely painting of her birdbaths in Where The Birds Are, I eliminated two photos which helped tell the story.

Interspecies bird feeding is unusual but not rare. The behavior is fueled by the powerful hormones which respond to the lengthening days in the spring.

Birds (male or female) may become a “helper” if their own nest is destroyed or if a bird is unable to find a mate. If nestlings have lost their parents and their calls are loud and persistent enough, a neighboring bird of another species may fill in as a parent.

Nestlings and fledglings learn their songs and calls from the feeding parents. Results can sometimes be disastrous as in the case where the helper, a gull of one species feeds gull of another species and the recipients no longer know when to migrate, I’m assuming our four juncos grew up to be proper adult juncos and didn’t leave for Mexico in the fall.

Where The Birds Are

In December each year, many in the country participate in the annual Audubon Christmas bird count. For the last ten years Samarkand has mustered up a dozen willing souls to walk Samarkand’s 16 acres to record the birds seen or heard. Half of their time was spent in Ann and Bob Allen’s Oak Crest garden, over the fence at the far end of the Native Plant Garden, where many species of birds come to visit their bird baths.

In the spring, local birds build their nests on the beams supporting the roof that overhangs part of their patio. Several years ago, when a pair of Dark-eyed Juncos were feeding their nestlings there, a stranger showed up with food in its beak. The Juncos chased off the intruder and then realized that a helper had shown up. The three birds fed the nestlings until they were old enough to leave the nest.

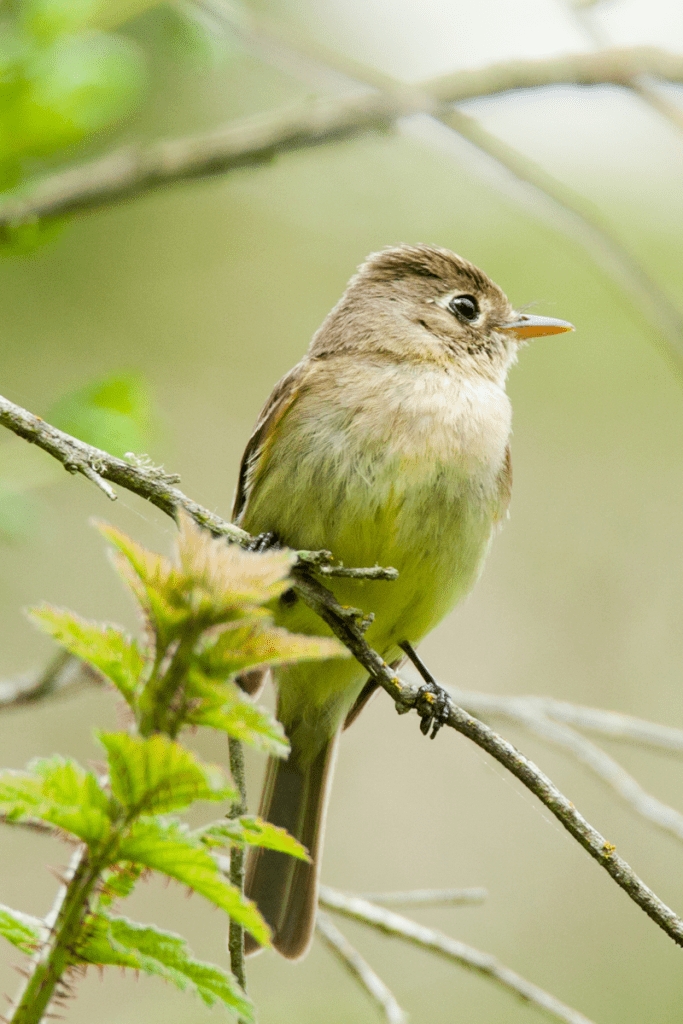

The stranger was a different species, a Pacific Slope Flycatcher with an upright posture and a slender beak for catching insects – a migrant who spent its winter in Southern Mexico. When the fledglings left the nest, the Flycatcher was out of a job. It called repeatedly for its lost family.

Come celebrate early summer at the Native Plant Garden, where you can enjoy orange poppies, blue and purple verbena, iris and fragrant sage. Stop at the sandstone fountain for wildflowers, birds and grand views.

September 22, 2022

This is one of the noteworthy days of the year, the fall equinox and the first day of fall. Like the spring equinox six months from now, day and night are roughly equal in length. The Bewick’s Wren is singing a more joyous song and the Oak Titmouse sings a combination of their spring halleluiahs with their raspy call notes. Nothing will come of it, of course, and the days will continue to grow shorter by two minutes a day until we are jolted by darkness falling by 7 PM.

In Santa Barbara on the south coast, a 100 miles west northwest of Los Angeles, fall doesn’t really show up until October, when the California grapevine turns red on the fence and the winter birds show up in the coastal gardens.

Over the last few days, Bay Area birders are plucking my heart strings by reporting the first Golden-crowned Sparrows of the season. I remember those chilly mornings in the Berkeley Hills when I would walk up the street towards the pasture whistling their song. If they had arrived in the early morning hours after a long night’s flight, they answered me with one or two minor key notes. I would yelp with joy and dance a quick jig. When I returned home, I made an entry in my notebook, circling the date in red.

It would be a few more days before the little flocks worked their way into the neighborhood to settle into their winter territories. I wondered if these birds were the ones that had come last year and maybe several years before. The good news was that they remained until mid or late April, developing the bright yellow crown, before departing for the far north. During the winter you could count on them singing just before it started to rain.

As far as I know there are no golden crowns in this neighborhood or even in Oak Park. They are most often reported in weedy fields in open areas like the upper Elings Park.

A single mature male has spent the summer feeding with several Song Sparrows in a clearing near Los Carneros Lake. Apparently, it declined to join the others of its kind for the migration north in April. Was he damaged in some way or simply lacked the normal instinct, the irresistible urge to migrate?

Hearing the Western Tanagers on the move, I will start listening for our winter birds, though I know it’s probably too early. I arrived at Samarkand as a reluctant migrant from Northern California at this time nine years ago. It was during the lull between the seasons. I was disconsolate. I looked for one familiar bird. Finally, there it was — a California Towhee scratching in the leaves alongside the pathway.

Something did arrive early this year, a substantial rain but with hardly a sprinkle here. Elsewhere, it was enough to signal the annual nuptial flight of the termites when some of these subterranean creatures grow a pair of gossamer wings for a day’s fling above ground in the bright air. The queen ascends high in the sky pursued by ardent males eager to mate with her. Then as quickly as it began, it was all over and the termites resumed their lives in the dark with a pregnant queen, leaving behind a shimmering carpet of discarded wings.

I had assumed this early storm was like the ones to follow, moving down the coast from the north. But the cause was Hurricane Kay, an extensive, well-organized storm which had originated off the coast of Baja California, slowly weakening as it moved north to bring varying amounts of rain.

Nature sent us a consolation prize though — a double rainbow which felt more like a gateway to grander things.

FALLING IN LOVE WITH ANGORA ALL OVER AGAIN

For many of us August is the vacation month. It is the last summer month before school begins again. We always headed for the mountains toward the end of August when it was often the foggiest time in the Berkeley Hills. It was less than a half-day’s drive to reach our vacation lake in the high Sierra.

I hope this story about our vacation will prompt you to remember your summer vacation, and maybe even write about it. Your family will love it.

When I learned that the Caldor fire last August had veered south, sparing Angora Lake, I was overwhelmed with gratitude. Had it taken a near miss to remind me of my 70-year devotion to this high Sierra Lake? A day later, Judith Hildinger, who with her brother Eric, runs the Angora Lakes Resort took the photo from her paddle board of a beautiful male Wilson’s Warbler sheltering in the mountain alder. Even though it was still smoky, I asked her to take more pictures around the lake’s edges because I wanted to write a long-overdue love letter to Angora.

I’ll start the photographic journey at the alder thicket next to the beach. The thicket had always been a safe place for nesting warblers in the summer. Not being able to penetrate the thicket from the beach, the best I could do was to push my boat as close to the shore as possible before being warded off by the wiry branches. I dropped my oars and sat listening to the small bird voices.

Beyond the mountain alders, an even denser pygmy forest of huckleberry oak, flows down the steep slope to the water’s edge. The huckleberry oak is the only high elevation oak in the big family of oaks, the most populous tree family in California. The huckleberry oak’s thin, flexible branches allow the tree to sprawl prostate over granite boulders. In a region of short summers, the acorn takes two autumns to mature. Once ripe, the little acorn is a favorite food of chipmunks and other small rodents.

It’s been years since I struggled up that slope to the ledge with the dwarf conifers where we had buried Don’s ashes. There was no other place he would have wanted to be.

It was a late afternoon in October when we arrived at the lake. The cliff and lake were in shadow. The cabins were boarded up and the boats stored away. I was anxious to be ahead of the first snow. It would have been next spring before we would have access again.

After tucking the ashes beneath a dwarf conifer on the first ledge, the girls and I returned to the beach. Jim stayed back as he grieved for his lost father.

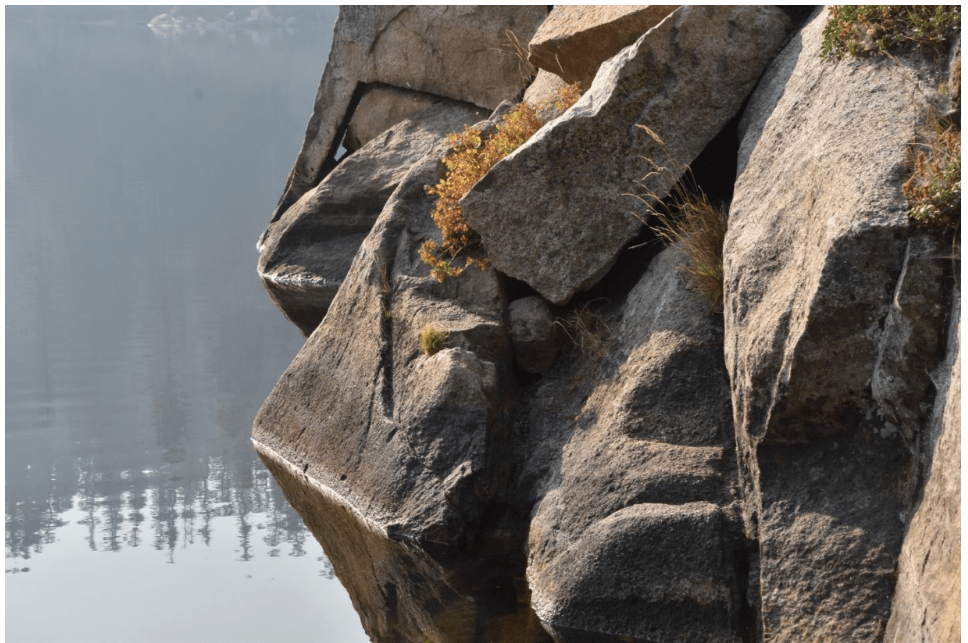

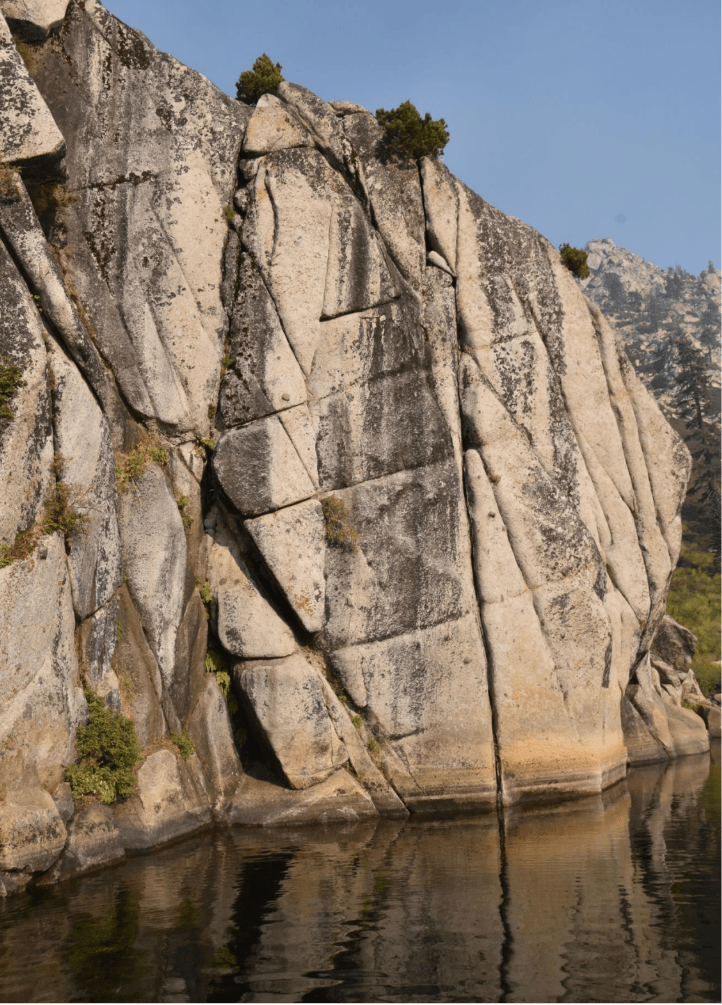

Around the corner from the oaks come the cliffs which distinguish upper Angora Lake from most other lakes. I always think this massive wall must be at least 10,000 feet high but in reality it reaches less than 9,000 feet, about 1,500 above the lake level. Sometimes even reality goes out the window when I think of Angora. Since I’m unable to travel any longer, Angora remains fixed in my mind and my heart and I want to get it right.

The cliff faces are streaked with chartreuse and dark brown lichens. By releasing an acid, the lichen slowly ingests the granite. Wherever there is a little soil in a crack, a seed or spore may take root producing delicate ferns or flowers. Further up on a face, a stout juniper with long ropy roots, has taken hold and found a home.

From the top at Echo Peak, the cliff descends to the lake interrupted only by occasional narrow ledges each with a miniature garden of quaking aspens, grasses and clumps of mountain ash with its vibrant red berries. Only in the driest years does water fail to trickle into the lake as miniature waterfalls. Often in late August a snow patch clings to the edge of the highest ridge.

One of the family rituals was to watch the rising sun first ignite Echo Peak with its golden light and then the sun slowly slides down the face to the lake level. I am always amazed how sunlight restores color, animating whatever it touches.

Just around the corner from where the cliffs end, a small grove of mountain hemlocks thrive in the cool shade. The hemlocks love the snow and winter. They often grow where the snow lasts the longest. John Muir wrote that if you were caught out in a blizzard, climb under the hemlock branches which reach down to the ground, and you will be sheltered.

I can’t remember the details of this north-facing shore of the lake. Of course there’s Frog Rock, the rock islet with its single tree. The steep slope of rocks and trees behind culminate in what we simply call The Ridge.

Ah, there’s something else about the ridge that allows me to stray off course. On a morning maybe sixty years ago when I was preparing breakfast on the wood stove with the door wide open, the roar of an engine startled me and I looked up to see a heavy-bodied two-engine plane skimming the ridge and dropping down over the lake, releasing a cloud of water filled with young trout. The plane pulled up abruptly and headed northeast toward Desolation Valley, delivering fish to other lakes.

Now, where was I? Oh, yes, near the cabins at the east end of the lake is a seasonal creek which links Upper and Lower Angora Lakes. When we were there in late August, the creek was usually dry, but I always enjoyed the sheltered ravine populated by some nice flowering shrubs like the Western Serviceberry and Western Spiraea. I liked to bring along a plant book for the satisfaction of giving a plant a name which always seemed to make it a friend.

One cabin, alone, occupied a space just south of the creek with a level place in front where you could pull up a boat. Though the cabin was too small for a family, I loved its separateness. It was one of the old-style cabins with a drop-down front which reminded me of my desk at home that concealed some of my treasures.

When the Forest Service revealed its plans to put in a campground on the site, the cabin was hoisted up on logs and eased across the creek to join the other cabins. Either the Forest Service came up short on money or the entreaties of people like us to leave the lake alone prevailed.

The other cabins were built side by side on a level area which may have been the glacial moraine formed during the time when glaciers scooped out the depressions which later filled with melting snow becoming the two lakes and the pond. When I think back to how this beautiful amphitheater, its cliffs, waterfalls, and peaks were formed, I wonder what the future holds. In a drier and hotter climate will the lakes become meadows or disappear altogether? And will the landscape, succumbing to fires, lose its conifers and become brush land or oak savannah? Will we have to ascend to 10,000 feet to find the Sierra we once loved?

I just looked at a random collection of photos taken by visitors of some of the handmade sign’s advertising: “The World-famous Lemonade;” “Angora Lakes Resort has been operating since 1917.” One photo showed a smiling Effie Hildinger, the original proprietress, who rode in on mule back in 1924. And a brown and yellow official Forest Service sign informed visitors that this is Angora Lakes Resort, National Forest Lands in the Lake Tahoe Basin.

My particular affection is for a cabin called The Lodge where we would have weekly slideshows in the summer. It was furnished with a well-used upright piano, chairs of various vintages and a loom. I spent many afternoons sitting on the small porch in the warm afternoon sun listening to various musicians — most often Gloria Hildinger on her flute, sometimes Jim Hildinger and his violin, and occasional visitors like Jan Popper on the piano and a cellist from Fallen Leaf on her cello.

And will I ever forget that early morning when Jim pulled his big speaker to the open doorway and filled the amphitheater with the glorious strains of Sibelius’ violin concerto.

Sibelius would have loved this place.

I sometimes walked the road down to Lower Angora Lake where occasional avalanches descending the steep slopes below Angora Peak would knock down a tree or two, blocking the road. I was always eager to visit one of the big red firs where the chartreuse, fragrant wolf lichen clinged to the ruddy bark. You can find the lichen mostly on the north side of the tree, just above the line where the trunk is free of snow. Lower Angora, with its scattering of cabins, lacks the dramatic setting of the upper lake.

Up the short hill is “Our House, ” the house where the Hildingers and their two young boys lived through winter in the 1930s. I remember one story where they would troop down to the ridge and holler down to the caretaker at Fallen Leaf Lodge and he would holler back. That was the social activity for the day.

“Our House” was distinguished by the aspen trees which grew close around the paned windows. The cabin was alive with dancing light when the leaves trembled in the slightest breeze. After lunch we would lie on the bed, listen to the voices of the kids below on the beach with the sparkling water reflected on the underside of the low eave.

I’m thinking of windy nights. The wind would come in gusts that sounding like an approaching freight train with spaces of eerie silence between. With our headboard against the single wall, we wondered if it would hold.

On this south-facing slope, the shrubs are very different from the mostly deciduous ones that grow in the protected swale along the creek. Just below the deck of “Our House” was a mountain chaparral garden composed as if by the most talented landscape designer. Several species shared the same slope – a low-growing silver-leafed plant called snow brush (Ceanothus cordulatus), a stunning bush Chinquapin with shiny yellowish leaves, more golden on the undersides with a spiny burr that encloses two or three seeds. One afternoon I discovered beneath the dense cover a hard-to-find bird I had never seen before: a Green-tailed Towhee.

It seems all paths led to the beach when our kids were little. The sand was a granular granite with sparkles of mica like that of the parent rock. The beach was narrow when the lake was high, usually in early summer, wide in the late summer when the lingering snow banks on the ridge had melted. I liked lying on my back and watching clouds moving over the peak toward the east. I speculated about whether a cloud would make it across my field of vision before dissolving. Fair weather clouds are generally short-lived.

It was at the beach that kids won a rite of passage – swimming across the lake and back. The reward was dad saying they no longer had to wear a life jacket when in a boat.

The other rite was to climb up the steep slope to the top of Echo Peak and then hollering “Echo” down to listeners below. As I recall, the reward for the climb was a cold glass of fresh lemonade.

We didn’t discover Angora by accident. It was a carefully engineered plan by my parents who once stayed at Angora when meals were served in the dining room by Jim and Effie. Once Jim went into the Army, the cabins were provided with modest cooking facilities, and the dining room was closed. My parents went elsewhere returning only for our inauguration.

We arrived in the afternoon, my parents greeting us at the doorway and my mother giving me instructions about how to be a good housekeeper, Angora style. “NEVER let any food particles go down the drain!” and with that, they departed down the hill in Jim’s truck as we would do for many years until our nest was empty.

Though our traditional week was the last week of August when the Berkeley Hills were the foggiest, we visited twice at other times for a day. Once was in June – spring in the Sierra when the meadows were wet and green and birds sang everywhere. Angora was transformed by robin song. By late summer, we were left with the harsh voices of Steller’s Jays and the chatter of squirrels and chipmunks. Toward the end of our stay, Clark’s Nutcrackers called as they began moving down from the higher mountains ahead of winter.

Probably the strangest visit to Angora was the first day of the new year before the arrival of the winter snows. The lake before us was frozen and the sun was about to set behind Echo Peak. Once the sun disappeared, we were cold. But what detained us was a deep growling sound coming from across the lake near the cliffs. What was that? Bear, mountain lion? Feeling unwelcome in this unfamiliar Angora, we hurried down the hill until near the Lookout ridge we regained the sun. Later, we learned we had heard the scrapping of the ice against the cliff. Maybe the sound was distorted and amplified by the ice itself or by the cold, deep water below.

Usually after a few days of being under the lee of the cliff, I was ready for some distant views. Walking down the hill to the pond and the big flat area open to the sky, I could see to the south the familiar shapes of the peaks around Carson Pass. The tall Jeffrey Pines are widely spaced. From the upper branches came the clear, three notes of the Mountain chickadee and the somnolent buzzy song of the Western pewee which always made me drowsy on warm Sierra afternoons.

I headed back up the hill for a nap.