I take pleasure in thinking about the Santa Barbara of 500 years ago, before the arrival of the first traders and the mission builders. From the breakwater, I look to the city and the mountains, mentally removing buildings, roads, railroads, and all other signs of human habitation except for a scattering of thatched huts of the original Chumash tribes. As hunters and gatherers, they lived lightly on the land.

Now I will take away all the non-native vegetation. Yes, that includes the palms, which are native only to Palm Springs oases; the eucalyptus, olive and pepper trees; the purple-flowered jacarandas; and all of the other non-native species which later found Santa Barbara to be a suitable home.

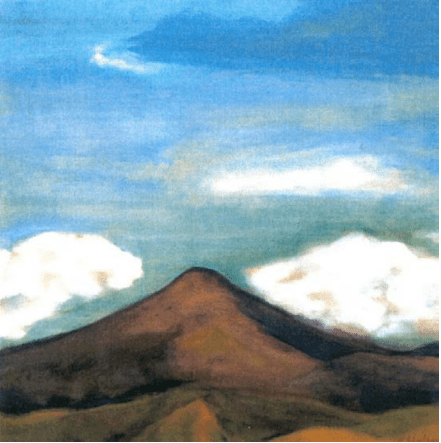

I now can see the bones of the landscape, the boulders and rock outcroppings. And the many creeks, most originating in mountain springs and fueled by winter rain. The creeks flow rapidly downhill and when reaching the flood plain, meander to the ocean.

The gentle sloping plain and surrounding hills are an oak savanna covered with grasses and scattered coastal live oak – a perfect habitat for grazing deer, elk and antelope who are stalked by wolves, mountain lions and grizzly bears, the most massive mammal of all.

In today’s Santa Barbara, the distant howl of a coyote or a rare sighting of a mountain lion reminds us of the wild past of our unique locale.