The First Rain

When my daughter and her family bought a house on a ridge looking directly into the Santa Ynez mountains, I was delighted. These are the canyons and mountains where my dad and grandfather used to explore and hunt when my dad was a boy. That first winter, when the rain clouds lifted, it revealed cliffs laced with waterfalls. In February, blooming chaparral dusted the mountains with white flowers and in April with blue blooms.

Chaparral is my favorite plant community, with its dense shrubs superbly adapted to long hot summers and short wet winters. The Santa Ynez mountains have their own climate, notably the sundowner winds which roar downslope raising temperatures and fanning fires. They are the western-most transverse range which is bent along the San Andreas fault, explaining why Santa Barbara faces south instead of west.

The mountain rocks are studded with fossils of sea creatures laid down from the millennia when the region lay under a warm sea. The rugged mountains cut off Santa Barbara from the north until late in the 19th century.

By Phila Rogers

The winter rains came late this year, with the first light rain falling the last day of February. Two robust storms followed the first week of March, giving us a seasonal total of eight inches. With only a scattering of rains since, that may be it until November.

We live in a Mediterranean climate characterized by a mild, wet winter and a hot, dry summer; a climate found only in southern and southwestern Australia, central Chile, coastal California, the Western Cape of South Africa and around the Mediterranean Basin. Despite extended periods of drought in the last decade, we had above-average rainfall for the last two years and our reservoirs are almost full.

I love our winter storms. Each one has its own personality. Some begin with a prelude of high wispy clouds made of ice crystals. Others sweep in on mid-level clouds and arrive on a counterclockwise wind from the southeast.

Here in Santa Barbara a winter storm brings the clacking of palm fronds and the pleasing odors of various sage. As an avid weather watcher, I wonder if spring will bring the May and June fogs or possibly something unusual, like a thunderstorm.

As the rainy season ends the landscape changes from green to gold. The grassland composed mostly of wild oats releases its seeds as the grass blades fade to a pale yellow. Fields of mustard grow tall and bloom with vivid yellow flowers. Many think of mustard as a native plant but in fact it arrived in California in the fur of long-horned cattle in the late 18th century. When the rains come again in the late fall, green will spread again across the landscape like a rising tide.

Illustration by Carol Anderson

When my 95th birthday came around in the first week of April, I suggested to my son that we take a ride over the mountains to the Santa Ynez Valley. In this second generous winter in a row when rainfall exceeded the annual normal, I was eager to see the green landscape. My son doubted I could see much.

But I had a new strategy. I would look carefully and then I would employ what I call “historical memory.” When I saw the elegant Valley Oak in its pasture I remembered from earlier times its far reaching branches and the scalloped leaves unfurling. I saw the black cattle and I recalled again how they stood belly deep in the fresh grass. When we passed a small tree with billowing pale blossoms, I knew it was a light blue ceanothus.

Life is different now that I have lost half my eyesight. It is a softer world, as if enveloped in a light haze. I’m taking out my paints again so I can show you what I mean and how each vivid orange poppy still calls attention to itself. And above all, the skies filled with April clouds truly speak to me with their vaporous edges and changing shapes.

I take pleasure in thinking about the Santa Barbara of 500 years ago, before the arrival of the first traders and the mission builders. From the breakwater, I look to the city and the mountains, mentally removing buildings, roads, railroads, and all other signs of human habitation except for a scattering of thatched huts of the original Chumash tribes. As hunters and gatherers, they lived lightly on the land.

Now I will take away all the non-native vegetation. Yes, that includes the palms, which are native only to Palm Springs oases; the eucalyptus, olive and pepper trees; the purple-flowered jacarandas; and all of the other non-native species which later found Santa Barbara to be a suitable home.

I now can see the bones of the landscape, the boulders and rock outcroppings. And the many creeks, most originating in mountain springs and fueled by winter rain. The creeks flow rapidly downhill and when reaching the flood plain, meander to the ocean.

The gentle sloping plain and surrounding hills are an oak savanna covered with grasses and scattered coastal live oak – a perfect habitat for grazing deer, elk and antelope who are stalked by wolves, mountain lions and grizzly bears, the most massive mammal of all.

In today’s Santa Barbara, the distant howl of a coyote or a rare sighting of a mountain lion reminds us of the wild past of our unique locale.

This is one of the noteworthy days of the year, the fall equinox and the first day of fall. Like the spring equinox six months from now, day and night are roughly equal in length. The Bewick’s Wren is singing a more joyous song and the Oak Titmouse sings a combination of their spring halleluiahs with their raspy call notes. Nothing will come of it, of course, and the days will continue to grow shorter by two minutes a day until we are jolted by darkness falling by 7 PM.

In Santa Barbara on the south coast, a 100 miles west northwest of Los Angeles, fall doesn’t really show up until October, when the California grapevine turns red on the fence and the winter birds show up in the coastal gardens.

Over the last few days, Bay Area birders are plucking my heart strings by reporting the first Golden-crowned Sparrows of the season. I remember those chilly mornings in the Berkeley Hills when I would walk up the street towards the pasture whistling their song. If they had arrived in the early morning hours after a long night’s flight, they answered me with one or two minor key notes. I would yelp with joy and dance a quick jig. When I returned home, I made an entry in my notebook, circling the date in red.

It would be a few more days before the little flocks worked their way into the neighborhood to settle into their winter territories. I wondered if these birds were the ones that had come last year and maybe several years before. The good news was that they remained until mid or late April, developing the bright yellow crown, before departing for the far north. During the winter you could count on them singing just before it started to rain.

As far as I know there are no golden crowns in this neighborhood or even in Oak Park. They are most often reported in weedy fields in open areas like the upper Elings Park.

A single mature male has spent the summer feeding with several Song Sparrows in a clearing near Los Carneros Lake. Apparently, it declined to join the others of its kind for the migration north in April. Was he damaged in some way or simply lacked the normal instinct, the irresistible urge to migrate?

Hearing the Western Tanagers on the move, I will start listening for our winter birds, though I know it’s probably too early. I arrived at Samarkand as a reluctant migrant from Northern California at this time nine years ago. It was during the lull between the seasons. I was disconsolate. I looked for one familiar bird. Finally, there it was — a California Towhee scratching in the leaves alongside the pathway.

Something did arrive early this year, a substantial rain but with hardly a sprinkle here. Elsewhere, it was enough to signal the annual nuptial flight of the termites when some of these subterranean creatures grow a pair of gossamer wings for a day’s fling above ground in the bright air. The queen ascends high in the sky pursued by ardent males eager to mate with her. Then as quickly as it began, it was all over and the termites resumed their lives in the dark with a pregnant queen, leaving behind a shimmering carpet of discarded wings.

I had assumed this early storm was like the ones to follow, moving down the coast from the north. But the cause was Hurricane Kay, an extensive, well-organized storm which had originated off the coast of Baja California, slowly weakening as it moved north to bring varying amounts of rain.

Nature sent us a consolation prize though — a double rainbow which felt more like a gateway to grander things.

After a rainless January and February, we were excited to learn that a storm was moving our way. I read that it was being carried down the coast by our old friend the “jet stream,” that fast-moving river of air moving from east to west which circulates around the globe often delivering weather systems to our coast. Or at least it used to.

The possibility of a storm deserved a morning sky watch. Soon after sunrise, I stepped outside on my balcony and aimed my camera at the sky and would continue to do so at hourly intervals until noon. As a long-time sky watcher (or storm watcher) in the Bay Area, the evidence was not encouraging.

Though winter storms generally form in the Gulf of Alaska and move down the West Coast, the winds that accompany them blow counterclockwise, so approaching storms are preceded by winds from the southeast. This morning the wind blew consistently from the northeast and was cold and dry, rather than moist and mild.

What I loved about most winter storms was the buildup that preceded the arrival of the storm itself. From my Bay Area hilltop house, I could scan the horizon from the south of San Francisco north past Mt. Tamalpais to Sonoma County. Not much escaped my attention.

The classical winter storm usually begins with high cirrus clouds often in fantastical shapes like wispy feathers. The clouds spread across the sky from north to south. At some point the wind begins, fluky at first before settling into gusts from the southeast growing in strength as the clouds thickened and lowered.

After years of living in Berkeley, I knew the wind direction without looking. An early October storm carried the strong, acidic odor of cooking tomatoes coming from the Heinz catsup plant in southwest Berkeley. If the wind was blowing from the northwest, it would carry the strong petroleum odors coming from the Chevron distillery in Richmond.

In Santa Barbara, where I have lived for 10 years, I smell mostly the odor of cooking tortillas and the scent of flowers. Sometimes the alarming smell of burning chaparral tells me there is a fire in the mountains. When the wind blows from the northwest during in the long summer, the air smells vaguely like ammonia or slightly salty of kelp drying on the beach. It feels heavy and damp.

I’ve often wondered why I am so exhilarated just before a storm. I dash around, bringing in outdoor furniture, rolling up outdoor shades and tying them tight. Hankering for the feel of soil, I plant that final sixpack of pansies ahead of the rain.

Now I’ve learned the likely cause of this joyous energy – negative ions. Negative ions associated with clouds and wind facilitate the transfer of oxygen to the cells. No wonder I’m so exhilarated. After a storm has passed, denied this extra oxygen, I descend into what I’ve always thought of as a post-storm slump.

None of this energy was associated with today’s morning’s storm watch which began with a few isolated clumps of white clouds and a wind that never shifted around to the southeast. Instead of the air warming as it usually does with an approaching storm, the wind rattling in the dry foliage was cold and odorless. By noon the clouds had mostly disappeared leaving only a few shards to help color the sunset.

Later I learned that the storm track was inland, bringing a dusting of snow to the higher coastal peaks while delivering generous, dry fluffy snow to the Sierra. I was disappointed after high hopes for a good rain, but I did enjoy the variety – a welcome relief from the still warm air from sunup to sunset.

TWO BOOKS FOR THE SKY WATCHER

The first book, sumptuously illustrated with clouds from around the world is titled: “The Cloud Collector’s Handbook,” by Gavin Pretor-Pinney. It is the official publication of The Cloud Appreciation Society. The Brits do love their weather. Some photos and descriptions are of familiar clouds. One is so rare you have to travel to the north-east corner of Australia to see it.

The second book is “Reading the Clouds: how you can forecast the weather,” by Oliver Perkins. He is another Brit, a sailor for whom knowing the weather is critical. One reason for “having your head in the clouds” is that they are full of valuable and interesting information.

Early November

The resident hawk

Repeats its urgent calls.

Where is the rain?

The temperature is above eighty.

Night falls with red skies

Color caught by the high cirrus clouds

Too thin for rain.

With darkness comes

The cricket stridulations,

The final notes of the fading season

After midnight I step out on my porch,

Looking high to the south.

Orion waits, trailed by Sirius,

The hunter’s faithful dog.

Venus will soon separate itself from the rising sun

And before month’s end will shine alone

In the eastern sky.

Once I’d imagined spending my final years

In the town where I was born

In a tiny house of my own design

One room only

With alcoves for bathing, sleeping, fixing tea

A steep roof with a skylight or two

A generous porch under a sheltering eave

High in the Berkeley Hills,

But instead, my final years

Will be spent in Santa Barbara

in a spacious apartment

One of many apartments

For elders like myself,

Close to family,

a hedge against loneliness.

The geographer in me

Wants to tell you

That Santa Barbara is located

At the southern end of central California.

Maybe 50 miles below Pt Conception

Where the coast bends inland

Thanks to the San Andreas Fault

Flexing its muscles.

So now the coastal mountains run

From east to west,

and most confusing of all

You look south if you want to see the ocean.

For me, the ocean has always been to the west,

And the direction of the setting sun

Where if you sail far enough

You’ll bump into China.

The high Santa Ynez Mountains to the North

shield the town from certain cold draughts.

But in downpours, the mountains

Shed all manner of debris

From silt to sandstone boulders

As big as cars.

Now as an amateur geologist,

I’ll tell you that this knoll

I call home, is surrounded

By flatter land referred to

As an alluvial fan,

Crossed by creeks that

Only show up when it rains.

Locals brag about the mild climate

Forgetting about those vehement moments

Of gale-force winds

Called sundowners.

Or what about the microbursts

Which have been known to knock a plane

Out of the sky?

And there’s nothing mild about my landscape.

Never still — it twists, heaves and cracks.

Worse, it is said that all the commotion

Is bringing Los Angeles ever closer.

Once we were covered by a warm sea

With dinosaurs wandering the shallows.

Later mountains rose up,

Full of seashells.

Now it seems that our future is drought.

I look out the east-facing windows

Down into Oak Park with its

Pale limbed-sycamores and faded foliage.

It’s a peoples’ park

With mariachis on the weekend

Shouting children,

Birthdays with piñatas

Quinceaneras, sometimes a funeral

Look up to the first ridge

To St. Anthony’s towers

And to the two rosy domes

Of the old mission.

Higher yet is the bulk

Of the Santa Ynez mountains

and the conical shape

Of my mountain – Montecito Peak

See how the angled sun

Deepens the canyons.

Slide your eyes sideways

To where the mountains

Slip into the blue line of the sea.

Now face south

Over our native garden

Bordered oaks from the park

To the silent creek bed.

I look for hummingbirds, bush rabbits

and worry about coyotes

The east hills, called the Mesa

Holds off the fog

Until after dark,

when the hills are breached.

Oh yes, my garden off the front door

The narrow porch of a garden,

Hung with red geraniums

And softened by pots of ferns

I lie in my bed beneath the windows

Hoping for wind to move the chimes.

I lift my head at dawn.

Do I see the silhouette of the mountains

Against the lightening sky?

Or are we cocooned in the fog

That drips from trees

Almost as welcome as rain.

And what is the first bird this morning?

The clink of the towhee

The querulous wren

The sweet ring of sparrows’ song?

Now you are hearing the voice of the birder

Leaning on every song

In the absence of good eyesight.

Acorn woodpecker, flicker

With strong beak and loud call,

Or the relentless caw of the black crow,

Boss of the neighborhood?

Will I be lucky enough

To have an owl’s hoot rouse me

In the early morning hour?

I feather my nest

With a down comforter

Books,

Bouquets of pungent sage,

Baskets of lichen.

How do I finish this short tale?

A day ending, I suppose.

With the dark coming on by five

A tale of rain arriving?

A gusty wind from the southeast

Testing itself.

In the early morning hours

Between midnight and dawn

The rain falls

I smell it first

And then sweet fragrance of hope

Could this be

The beginning of a season

Of abundant rains

Enough to end the drought?

COMING IN THE SPRING: The Best for Last: The Nature of Santa Barbara by Phila Rogers. Includes the blogs and a number of short pieces.

After such a sumptuous winter how could it not be – a perfect spring.

I came to Santa Barbara to live in September 2013, the second year of the drought. The landscape was dry, but as a native Californian, I expected dryness. The winter rains the next two years were scanty. Not only did the garden lawns die by intent, but landscape and street trees began suffering. Many of the redwoods, never a good choice for this semi-arid climate, were dying. The conifers were the hardest hit. The native ponderosa pines on Figueroa Mountain all succumbed, probably weakened by the drought and then attacked by the deadly bark beetle. To try and save street trees, the city attached green plastic reservoirs to young trees which slowly released water to the roots.

Maybe several times during the winter, enough rain would fall to feed the headwaters of various creeks. Mission Creek with its springs high on mountain sides above the Botanic Garden came briefly to life with muddy torrents of water which rushed down the dry creek bed. Quickly depleted, the flow stopped and by the second day, the creek became isolated pools. By the third day, the creek disappeared all together.

With the return to silent stretches of dry rock, my spirits fell. I realized again how above all the landscape features – hills, mountains, valleys, and especially the noisy, restless ocean – it is creeks I love the best, for their cheerful sounds and their ability to be a magnet for surrounding life.

Spring in California is mostly about wildflowers, but in one of the ironies of a wet spring, grass and weeds growing tall often concealed the flowers. Figueroa Mountain had some nice displays, particularly where lupine grew on perennial shrubs or where poppies grew on serpentine soil which inhibits the rampant growth of grass.

But it is in the exuberance of the commoner plants that I saw the results of a wet winter. The wild oats, now going to seed are waist high, and must compete for space with wild radishes and Italian thistle.

After four years of drought that tested their endurance, allowing no luxury like new growth, live oaks this spring were transformed with explosions of tender bright green leaves. The shiny leaves concealed the coarse and somber, dark green foliage, some of which could now be shed.

Live oaks are the most abundant native tree of Samarkand, Oak Park and most lowland locations.

Best of all was to see Mission Creek behaving like a real stream, not with just the episodic flow of two days that followed a rain during the preceding drought years. My morning ritual was to look through my binoculars into the small gap between the trees where I could see the overlapping brightness of moving water. The stream had a rhythm, sometimes squeezing around rocks making music and then released, spreading out in quiet pools, before being narrowed again. I think I could write a score with the proper notations.

I imagine my father, who grew up near Oak Park, capturing tadpoles with a net, or creating a new flow by rearranging rocks. When the flow was strongest, he and his buddies, no doubt, fashioned boats and then ran along the creek edge to see how they fared.

Two weeks after the last rain in March, the flow began to shrink, imperceptivity at first. But now in mid-April the creek has disappeared. Or, perhaps it flows beneath the surface still accessible to the roots of trees.

Speculation has already begun about next winter. Through summer and early fall, conditions appear to be “neutral” with early signs of building El Nino conditions beginning later in the fall. In most years, a strong El Nino brings generous rains, but not always. Speculation, especially about future weather, is irresistible especially for weather buffs like myself.

When one of my friends fell on an icy path this morning and Gibraltar Dam flowed into its spillway, the first time since 2011, I decided that winter could not be ignored.

I hadn’t considered writing about Santa Barbara in the winter thinking that the season had been mostly passed by in these years of drought. Then yesterday, December 23, we had a storm that was worthy of qualifying as a winter storm in every way. The day began with a thin cloud cover which built during the morning to promising layers of clouds and brief gusts of wind, which by noon led to rain. After slacking off in a way that I had become used to during these dry years, the rain built again as if to defy my pessimism. By mid-afternoon the rain built to a real gully-washer. I was lucky enough to be in my car so I could enjoy splashing through flows of water at every intersection and best of all, seeing Mission Creek coursing down its creek bed after so many months of being bone dry.

From the sound of my bamboo wind chimes during the night, I knew the storm had passed to the east and the wind had shifted to the north as it does along the coast after a rain storm. The cold wind continues today pushing around remnant clouds, now empty of their contents.

I know storm must follow storm to make the creek a winter feature and the soil be soaked enough to start recharging the depleted water table. Lake Cachuma which lies in the valley between our mountains, the Santa Ynez, and the higher range to the east, is the reservoir which holds our water supply. At present, it’s almost no lake at all, having shrunk to less than 7% of its capacity. Vultures have taken to roosting on the rim of the dam.

December ended with the rainfall slightly above normal.

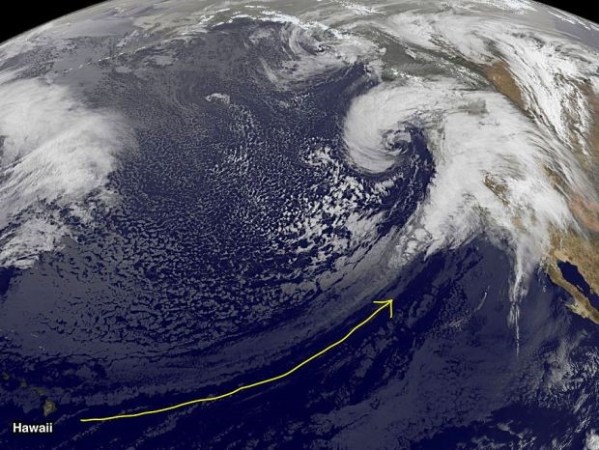

January was another matter altogether thanks to massive storms brought across the Pacific by an atmospheric river — a new word in my weather lexicon. An atmospheric river can be several thousand miles long to a few hundred miles wide. Drawing up moisture from near the Hawaiian Islands, the warm air can transport large amounts of rain. It’s what we once called the “Pineapple Express.’

The atmospheric rivers produced five days of good rains. At the end of January, rainfall for the month was 8.96 inches rather than a normal 2.86 inches. Even the lawns, most of which were allowed to go brown over the summer and fall, were green again.

The rains continued intermittently until Friday, February 17. The papers were advertising that the biggest storm of the season was on its way. Over the years, I have learned to be suspicious of such a build-up which often leads to disappointment. I believe in sneaker storms – the ones which arrive with little or no advance warning. That may be the old days before sophisticated weather-measuring equipment and computers, which can put together predictive models, eliminated much of the guesswork.

At 5 AM heavy rain was falling, serious, confident rain. By mid-morning the velocity of the rain continued to increase. Coarse and dense raindrops were being driven by gale winds from the south-east. By early afternoon, the rain had slackened enough to allow me to drive down to the Mission Creek just below us. Others had already gathered. Some of us stood on the bridge itself which was trembling with the force of the volume of water pouring a few feet beneath. On the opposite side of the bridge where the stream bed is narrowed by rock walls, boulders were being slammed together. The percussive, booming sounds resembled thunder. Some people, unnerved by the violence, hurried back to their cars. As a fan of such drama, I stayed put.

The storm finally moved on leaving 5-inches of rain downtown and heavier amounts on the mountain slopes. Mission Creek up Mission Canyon left its stream bed and temporarily carved out a new route. Further engorged by a cargo of mud, the stream poured over the old Indian Dam.

The gift for me was that Mission Creek became a real stream, a winter stream which flowed for weeks on end, not just for a day or two after a rain.

Now it’s early April and the creek has ceased to flow. It survived for few more days as isolated pools, until it disappeared altogether. I like to think that it continues to flow underground bringing moisture to the roots of the sycamores and to the other streamside plants.

Rattlesnake Creek, a tributary of Mission Creek in flood conditions.

Credit: Ray Ford

(Please note the material following the video is not part of this presentation.)