I had written a nice enough short piece about the native plant garden in early summer to run on my website, and then the piece disappeared from my computer—forever.

I had commented on looking down into the garden and seeing a scattering of California poppies and two white flower spires, the last of the “candelabras” on top of the buckeye tree. The buckeyes growing on the drier slopes around lowland California are one of the only trees which drop their leaves in late summer rather than in the fall. The buckeyes are not preparing for winter like most deciduous trees but to avoid the heat of late summer and early fall. Their large thin leaves can’t take the heat. But once bare, there is a new beauty to behold – an intricate design of smooth, light gray crooked branches. Donald Culross Peattie in “A Natural History of Western Trees” calls the California Buckeye “an oddly lovely tree.”

Happy is the hiker who carries a dense smooth buckeye seed in one pocket and a sprig of fragrant California sage in the other.

What I can’t see looking down from my bacony is the bright fuchsia and white splash of color of the clackias (“farewell-to-spring”)– usually the final wildflower display of the spring wildflowers. This has been a banner year for wildflowers following the winter of generous rains. Now is the season for the pungent sages and the color purple. Sturdy bushes of “Alan Pickering” salvia with its powerful aromas must be a clarion call for pollinators.

The garden is shutting down for the season with the quiet business of ripening berries in the sun and roots searching for pockets of moisture.

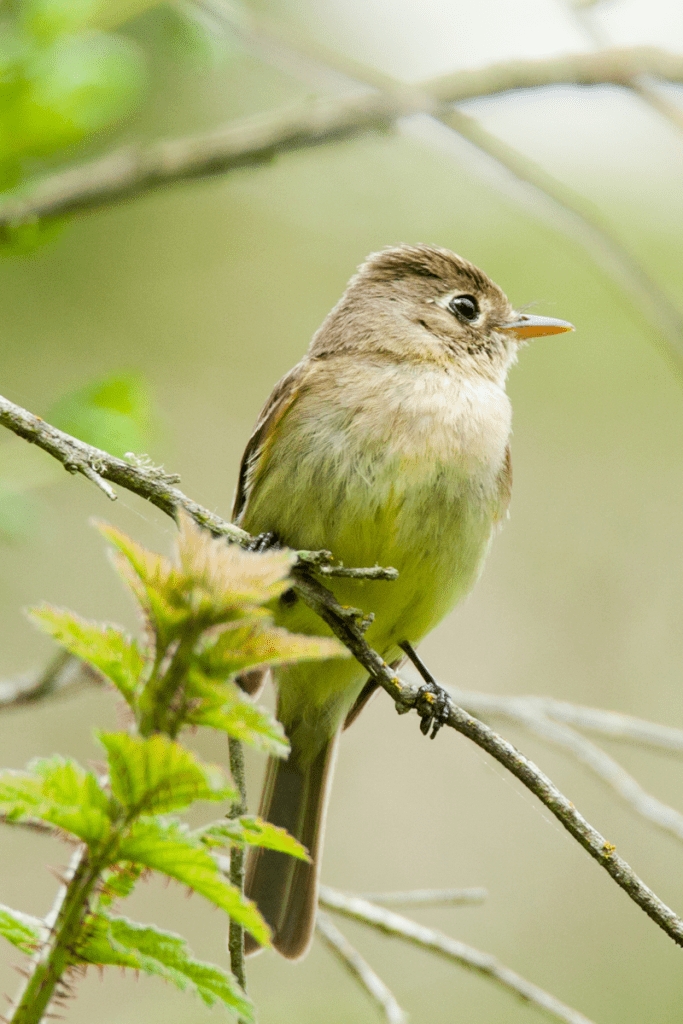

Seeing the surrounding gardens of bougainvillea, birds-of-paradise and hibiscus, folks complain about the native garden as being “drab.” I like to sit quietly on a bench and watch the antics of the fence lizards doing their pushups or waiting for the quiet drift of a butterfly which, like the birds, find the garden more interesting than the cultivated ones. Animals come to the garden, too. A bobcat passes through and once a mountain lion made a brief appearance.

I like the idea of matching our natures to the natural rhythms of nature itself.

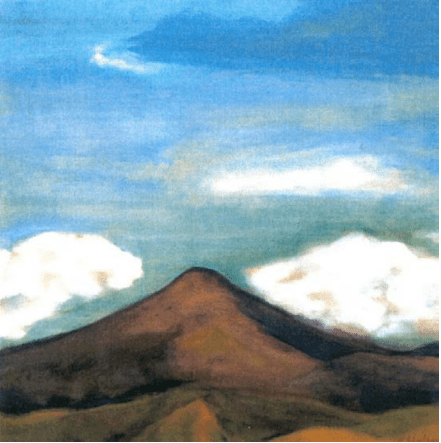

And I can’t resist commenting on the unusual weather (is there such a thing as “usual” weather?) It appears that the long, cool wet winter has slid almost seamlessly into a cool moist early summer with an abundance of clouds. In the Sierra, the days remain in the low 60s with regular afternoon showers and in the Central Valley the temperature rarely rises above 80 degrees, a welcome relief from the normal summer heat. Here on the coast, it is best described as gloomy and grayer than usual. This pattern is likely to change soon.