santa barbara

So Much More

We love our Samarkand campus with its 16 acres of cultivated gardens and trees located on a knoll above Mission Creek with wide views of the mountains.

But there is so much more.

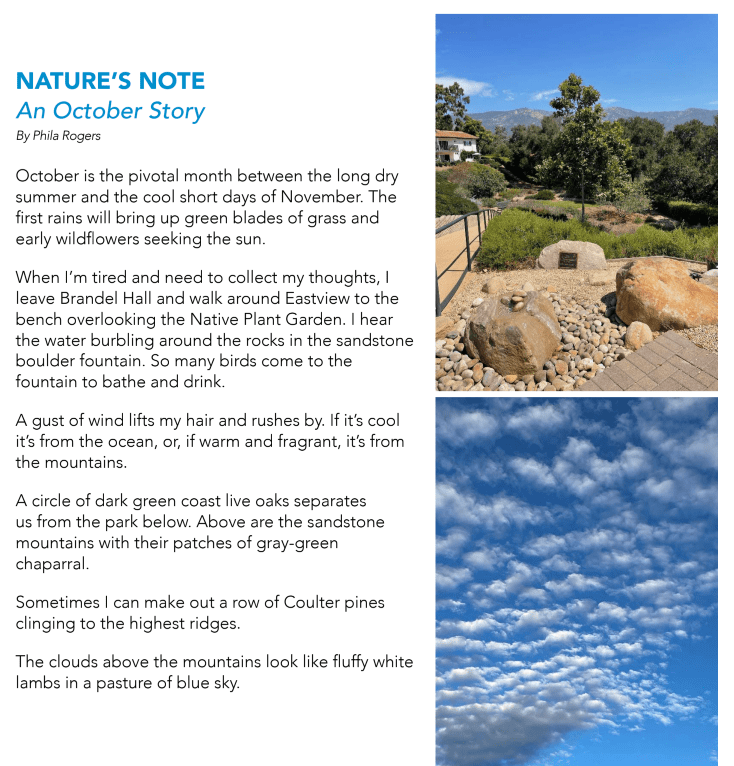

Our one-acre native plant garden captures the floral beauty of coastal California. A fountain made from a sandstone boulder attracts birds to drink and bathe and is a lovely place to sit overlooking the garden with the mountains beyond.

Samarkand is also an arboretum with its 350 trees, many of which are labeled. There is an accompanying Tree Map available in the nature corner in the library. On the self-guided tour, as you linger at each tree, you can imagine the complex system of roots underfoot and the miles of fungal fibers uniting them.

The nature corner in the library features books and field guides on the natural history of our area. You will also find a weather monitor that gives real-time weather specifically for our campus. Our Samarkand weather station is located on the roof of the Mountain Room.

The Mountains Above Us

When my daughter and her family bought a house on a ridge looking directly into the Santa Ynez mountains, I was delighted. These are the canyons and mountains where my dad and grandfather used to explore and hunt when my dad was a boy. That first winter, when the rain clouds lifted, it revealed cliffs laced with waterfalls. In February, blooming chaparral dusted the mountains with white flowers and in April with blue blooms.

Chaparral is my favorite plant community, with its dense shrubs superbly adapted to long hot summers and short wet winters. The Santa Ynez mountains have their own climate, notably the sundowner winds which roar downslope raising temperatures and fanning fires. They are the western-most transverse range which is bent along the San Andreas fault, explaining why Santa Barbara faces south instead of west.

The mountain rocks are studded with fossils of sea creatures laid down from the millennia when the region lay under a warm sea. The rugged mountains cut off Santa Barbara from the north until late in the 19th century.

A Meager Winter

By Phila Rogers

The winter rains came late this year, with the first light rain falling the last day of February. Two robust storms followed the first week of March, giving us a seasonal total of eight inches. With only a scattering of rains since, that may be it until November.

We live in a Mediterranean climate characterized by a mild, wet winter and a hot, dry summer; a climate found only in southern and southwestern Australia, central Chile, coastal California, the Western Cape of South Africa and around the Mediterranean Basin. Despite extended periods of drought in the last decade, we had above-average rainfall for the last two years and our reservoirs are almost full.

I love our winter storms. Each one has its own personality. Some begin with a prelude of high wispy clouds made of ice crystals. Others sweep in on mid-level clouds and arrive on a counterclockwise wind from the southeast.

Here in Santa Barbara a winter storm brings the clacking of palm fronds and the pleasing odors of various sage. As an avid weather watcher, I wonder if spring will bring the May and June fogs or possibly something unusual, like a thunderstorm.

As the rainy season ends the landscape changes from green to gold. The grassland composed mostly of wild oats releases its seeds as the grass blades fade to a pale yellow. Fields of mustard grow tall and bloom with vivid yellow flowers. Many think of mustard as a native plant but in fact it arrived in California in the fur of long-horned cattle in the late 18th century. When the rains come again in the late fall, green will spread again across the landscape like a rising tide.

Illustration by Carol Anderson

Our Avian Fellow-Traveler, the House Sparrow

By Ted. R. Anderson

The House Sparrow originally inhabited a broad geographic region stretching across Europe and North Africa and throughout most of Asia except mainland China. It lived in close association with people in both rural and urban communities and is now often referred to as an “obligate commensal” of human beings, meaning that it is dependent on its human neighbors.

The House Sparrow originally inhabited a broad geographic region stretching across Europe and North Africa and throughout most of Asia except mainland China. It lived in close association with people in both rural and urban communities and is now often referred to as an “obligate commensal” of human beings, meaning that it is dependent on its human neighbors.

When large numbers of people fled Europe in the mid-19th century to live on other continents, many missed their familiar avian neighbors, including the House Sparrow. In the mid-1800s, 100 sparrows were brought to the United States from England aboard the Europa and released in Central Park. With the help of subsequent introductions, the species spread across the continent, making their way to the Pacific coast by 1915. Similar introductions followed in Australia, Argentina and South Africa. Range expansions increased widely from each of these sites so that today the House Sparrow is widely distributed on every continent except Antarctica.

The House Sparrow is not common on the the Samarkand campus, but a lone male does spend much of each day repeatedly chirping near the entrance to our Smith Health Center, hoping, no doubt, to attract a female to his chosen nest site. My favorite place for sparrow-watching, however, is Renaud’s. Carol and I each order one of their fabulous pastries and a cup of coffee and sit in the outdoor patio. There I watch the sparrows hop around under the

tables picking up crumbs that fall to the ground as patrons eat their pastries. Clearly sparrows have good taste!

Ted Anderson is a retired professor of Avian Biology, and the author of “Biology of the Ubiquitous House Sparrow” (Oxford University Press). The watercolor of the house sparrow (above) was painted by Carol Anderson, Ted’s wife.

Phila Rogers is now 96 years old and legally blind. She has decided to occasionaly have some guest columns of which this is one.

My New Nest

It wasn’t that I outgrew my Eastview apartment, with its spacious rooms and expansive views, it outgrew me. With my dimming eyesight, I no longer could see the Mission bell towers and could barely discern the shape of Montecito Peak. From my new apartment at Brandel Hall, I have a pleasant view of trees, south sun, and flocks of musical goldfinches. Instead of woodpeckers visiting my suet, I have overwintering warblers with their more modest appetites.

Moving to a studio apartment, gave me a chance to “lighten my load.” I kept my favorite painting of a snowy mountain range with an Indian encampment in the foreground inspiring me to decorate my apartment in a style I call neo-tepee, allowing me to use my collection of hanging rugs, pots and woven baskets.

I am not the only January nester. The small Anna Hummingbirds and the large Great Horned Owls also build their nests in January. The hummingbirds fashion their nests from grasses and spiders web decorated with lichens while the owl builds a casual structure from sticks piled up in a tall tree.

Celebrating the Trees of Samarkand

I’ve discovered I’m not alone in choosing to live at the Samarkand for its natural beauty. Located on a knoll with Mission Creek at its base, there are wide views of the mountains and glimpses of the ocean. But mostly it’s for the gardens that bloom and an abundance of trees worthy of an arboretum.

The biggest California Live Oaks on the property once provided the acorns that the Chumash women would grind with their mortars and pestles into the meal that was the staple of their diet. The giant Southern Magnolia and the nearby koi pond date back to the elegant Samarkand Hotel that opened in 1921.

Recently, several of us took a walk around the 16 acres of our campus. We counted approximately 350 trees representing 36 species. Our fellow resident Craig Smith, an engineer who lives with his wife Nancy in Magnolia East, has co-authored two books

on the science behind climate change. Utilizing this information, he computed the amount of carbon dioxide sequestered (absorbed from the atmosphere) by the trees on our campus to be an amazing 14 metric tons annually. He also noted that our California Live Oak is the most efficient at absorbing carbon dioxide.