trees

The Mountains Above Us

When my daughter and her family bought a house on a ridge looking directly into the Santa Ynez mountains, I was delighted. These are the canyons and mountains where my dad and grandfather used to explore and hunt when my dad was a boy. That first winter, when the rain clouds lifted, it revealed cliffs laced with waterfalls. In February, blooming chaparral dusted the mountains with white flowers and in April with blue blooms.

Chaparral is my favorite plant community, with its dense shrubs superbly adapted to long hot summers and short wet winters. The Santa Ynez mountains have their own climate, notably the sundowner winds which roar downslope raising temperatures and fanning fires. They are the western-most transverse range which is bent along the San Andreas fault, explaining why Santa Barbara faces south instead of west.

The mountain rocks are studded with fossils of sea creatures laid down from the millennia when the region lay under a warm sea. The rugged mountains cut off Santa Barbara from the north until late in the 19th century.

Celebrating the Trees of Samarkand

I’ve discovered I’m not alone in choosing to live at the Samarkand for its natural beauty. Located on a knoll with Mission Creek at its base, there are wide views of the mountains and glimpses of the ocean. But mostly it’s for the gardens that bloom and an abundance of trees worthy of an arboretum.

The biggest California Live Oaks on the property once provided the acorns that the Chumash women would grind with their mortars and pestles into the meal that was the staple of their diet. The giant Southern Magnolia and the nearby koi pond date back to the elegant Samarkand Hotel that opened in 1921.

Recently, several of us took a walk around the 16 acres of our campus. We counted approximately 350 trees representing 36 species. Our fellow resident Craig Smith, an engineer who lives with his wife Nancy in Magnolia East, has co-authored two books

on the science behind climate change. Utilizing this information, he computed the amount of carbon dioxide sequestered (absorbed from the atmosphere) by the trees on our campus to be an amazing 14 metric tons annually. He also noted that our California Live Oak is the most efficient at absorbing carbon dioxide.

The Arboreal Internet

Before taking a deep dive underground, I must pay tribute to leaves for their remarkable abilities. If a predator begins munching on the leaves of one tree, that tree sends a chemical signal to nearby trees warning them to mount their defenses. The neighboring trees respond by sending substances into their leaves which makes them unpalatable. And it is in the leaves where photosynthesis takes place by combining water, sunlight and absorbed carbon dioxide to produce sugar, the staple food for the tree and nutritional support for nearby trees in need through the mycelium network under the ground.

The Underground Network

scattered spores keep the mycelium growing

(Illustration courtesy Kauai Seascape Nursery)

Mycelium are threadlike strands of fungi that attach themselves to tree roots of different species, creating what one researcher calls “nature’s world-wide web.” Trees have a way of communicating with one another. They can send nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus to an ailing neighbor, making up part of the vast system that supplies water and nutrients to undernourished trees nearby. And the underground network also sends warning messages and alerts about impending conditions like drought.

Understanding the language of trees is an ever-expanding field of research, and for the student like myself, this knowledge deepens my awareness of trees. No longer can I consider trees non-sentient beings as I once believed. Their own particular form of “intelligence” may help trees survive in a changing world.

The Wind in the Trees

I love the wind, the way it animates the landscape by setting trees into motion and sends clouds scudding across the sky. Samarkand is not only a senior living facility, but also an arboretum, with 350 individual trees representing 35 species, many of them labeled. Here I can further hone my skills identifying trees. As Canary Island Pines sift the wind with their slender needles, they murmur and sigh. With their long leathery leaves, blue gum eucalyptus trees sound in a good wind like falling water. The palms are the noisiest of all, and their colliding fronds remind me of the sound of a downpour falling on a metal roof.

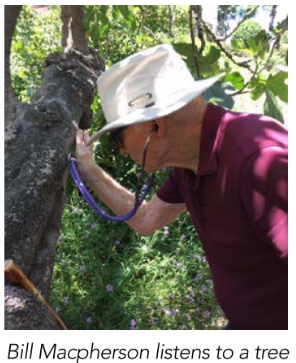

Recently, three of us decided to listen to trees in a different way. We engaged retired doctor Bill Macpherson and his stethoscope to hear the sounds produced by both a redbud and a sycamore tree that were each producing a new crop of fresh leaves. Pressing the cup of the stethoscope against the thin bark, we each got different results. Bill heard a sound like water rushing up a pipe. I heard faint popping sounds and a low-pitched gurgle. Ann Allen, perhaps less susceptible than Bill and I, heard nothing. We plan to wait for a hot day and try again.

A Softer World

When my 95th birthday came around in the first week of April, I suggested to my son that we take a ride over the mountains to the Santa Ynez Valley. In this second generous winter in a row when rainfall exceeded the annual normal, I was eager to see the green landscape. My son doubted I could see much.

But I had a new strategy. I would look carefully and then I would employ what I call “historical memory.” When I saw the elegant Valley Oak in its pasture I remembered from earlier times its far reaching branches and the scalloped leaves unfurling. I saw the black cattle and I recalled again how they stood belly deep in the fresh grass. When we passed a small tree with billowing pale blossoms, I knew it was a light blue ceanothus.

Life is different now that I have lost half my eyesight. It is a softer world, as if enveloped in a light haze. I’m taking out my paints again so I can show you what I mean and how each vivid orange poppy still calls attention to itself. And above all, the skies filled with April clouds truly speak to me with their vaporous edges and changing shapes.

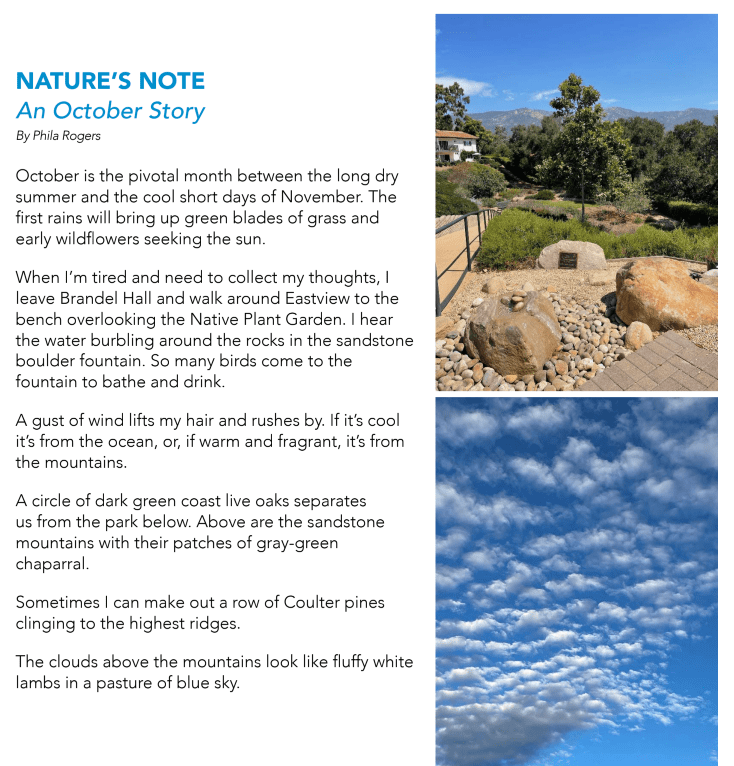

Autumn In Santa Barbara? Yes!

Maybe we can’t brag about brilliant splashes of color everywhere like they can back east, since Fall is subtler in California, but there are still clear signs that the seasons are changing. As the days grow shorter, shadows grow longer, giving a rich, baroque look to the landscape. The air achieves a balance between the cool, damp marine flow and the drier air of the mountains. The breeze has a tantalizing sweetness of ripening fruits and crumbling leaves.

In the Native Plant Garden behind Eastview, you’ll see the billowy bushes of the Toyon, whose succulent berries will be red by Christmas. Further down is the sprawling “Roger’s Red,” a subspecies of the California wild grape. The White-crowned Sparrows arrived in October and fill the garden with their sweet songs.

In Oak Park, the leaves on the big sycamores are tawny now. Around town, you’ll see liquid amber trees, with a palette of oranges and maroons, and the ginkgo trees will soon turn a pure brilliant yellow. The lone survivor of an ancient species, these trees shared a landscape with the dinosaurs.

Fall is not just about plants. It’s also about critters—the big Orb Weavers that weave symmetrical webs and then plant themselves in the center waiting for trapped insects. And if you find yourself in the dry country, look for the astonishing sight of tarantulas on the trails in search of mates.

The Trees Above Us

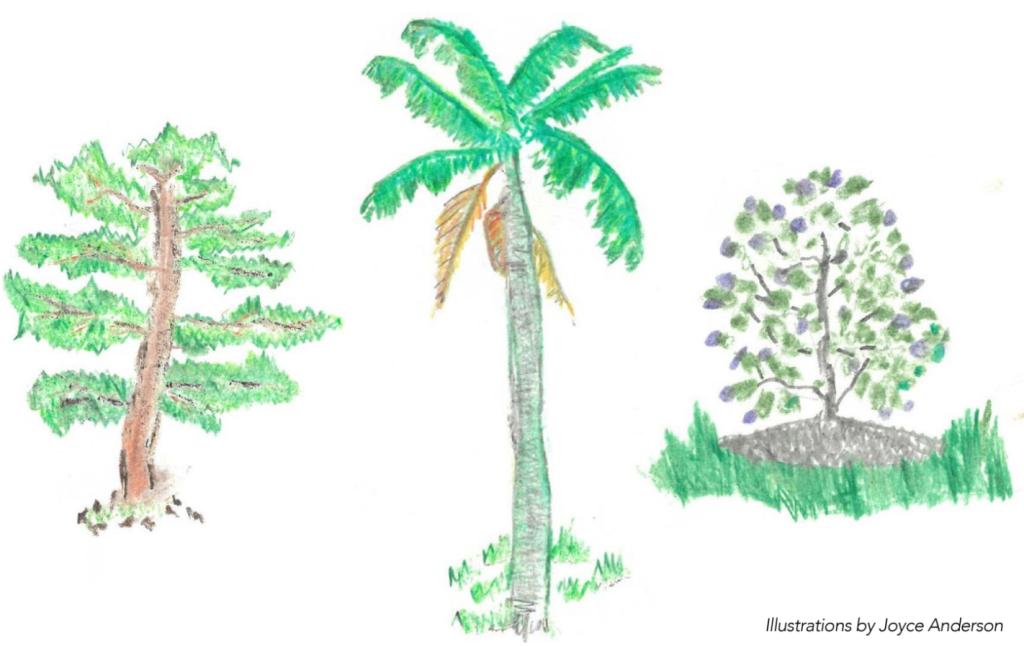

We love our trees at Samarkand. And no wonder. There are about 350 of them on campus, representing 36 different species. Some have seasonal flowers; others are deliciously fragrant even without blooms. One is tall enough to “dust the sky.” Others are broad enough to provide shade on hot days. They give form and shape to the cultivated semi-tropical gardens that grace our 16-acre knoll.

No wonder so many people come here for their final days!

Joyce and Allan Anderson, Magdy Farahat and I worked together to gather information to create labels for many of the trees around the campus. The labels will have both the common and the scientific names of the trees and will be large enough to be easily read. We plan to create a map showing the location of these trees.

Once Upon A Time

I take pleasure in thinking about the Santa Barbara of 500 years ago, before the arrival of the first traders and the mission builders. From the breakwater, I look to the city and the mountains, mentally removing buildings, roads, railroads, and all other signs of human habitation except for a scattering of thatched huts of the original Chumash tribes. As hunters and gatherers, they lived lightly on the land.

Now I will take away all the non-native vegetation. Yes, that includes the palms, which are native only to Palm Springs oases; the eucalyptus, olive and pepper trees; the purple-flowered jacarandas; and all of the other non-native species which later found Santa Barbara to be a suitable home.

I now can see the bones of the landscape, the boulders and rock outcroppings. And the many creeks, most originating in mountain springs and fueled by winter rain. The creeks flow rapidly downhill and when reaching the flood plain, meander to the ocean.

The gentle sloping plain and surrounding hills are an oak savanna covered with grasses and scattered coastal live oak – a perfect habitat for grazing deer, elk and antelope who are stalked by wolves, mountain lions and grizzly bears, the most massive mammal of all.

In today’s Santa Barbara, the distant howl of a coyote or a rare sighting of a mountain lion reminds us of the wild past of our unique locale.

Celebrating California Oaks

Californians love to brag about their trees. We will tell you that we have the tallest, most massive and the oldest trees in the world – the coast redwood, the Sequoia redwood growing in the midSierra and the bristlecone pine which is found in a small area of the White Mountains east of the Sierra.

In my view, we should save our bragging rights for our native oaks – the 20 species (40 if you count the hybrids). some of which only grow in our state. I give my vote to our coastal live oak. This evergreen oak is only found along the coast from Mendocino County to Baja California. The nutritious acorn was the staple food for the Chumash. The women ground the acorns in their stone mortars and rinsed out the bitter tannins in running water. (Now that I’ve found a source of acorn flour, I’m going to try my hand at baking acorn bread).

The coast live oak is the commonest tree species on our campus with three individuals distinguished by their size. One tree, 50 feet wide, spreads across the Life Center courtyard with a luxuriant canopy of small leaves; a second is located in the large lawn below Westview and Northview; and the third, the largest, is next to the Rose Garden with an 80-foot-wide canopy and a stout trunk measuring ten and half feet in circumference. Most often, the oaks are sprouted from an acorn buried by a scrub jay and then forgotten about.

Thank you, Jesus and Pedro for measuring the circumference of the three largest oaks!